Yuma County, Colorado

Photographs

Yuma County, Colorado |

|

| Home Page | Photograph Index | Site Index |

LOUIS A. and ELEANOR. V. (SHAVER) HARUF, daughter EDITH (HARUF) RUSSELL, sons VERNE and MARK and ALAN KENT HARUF, Yuma

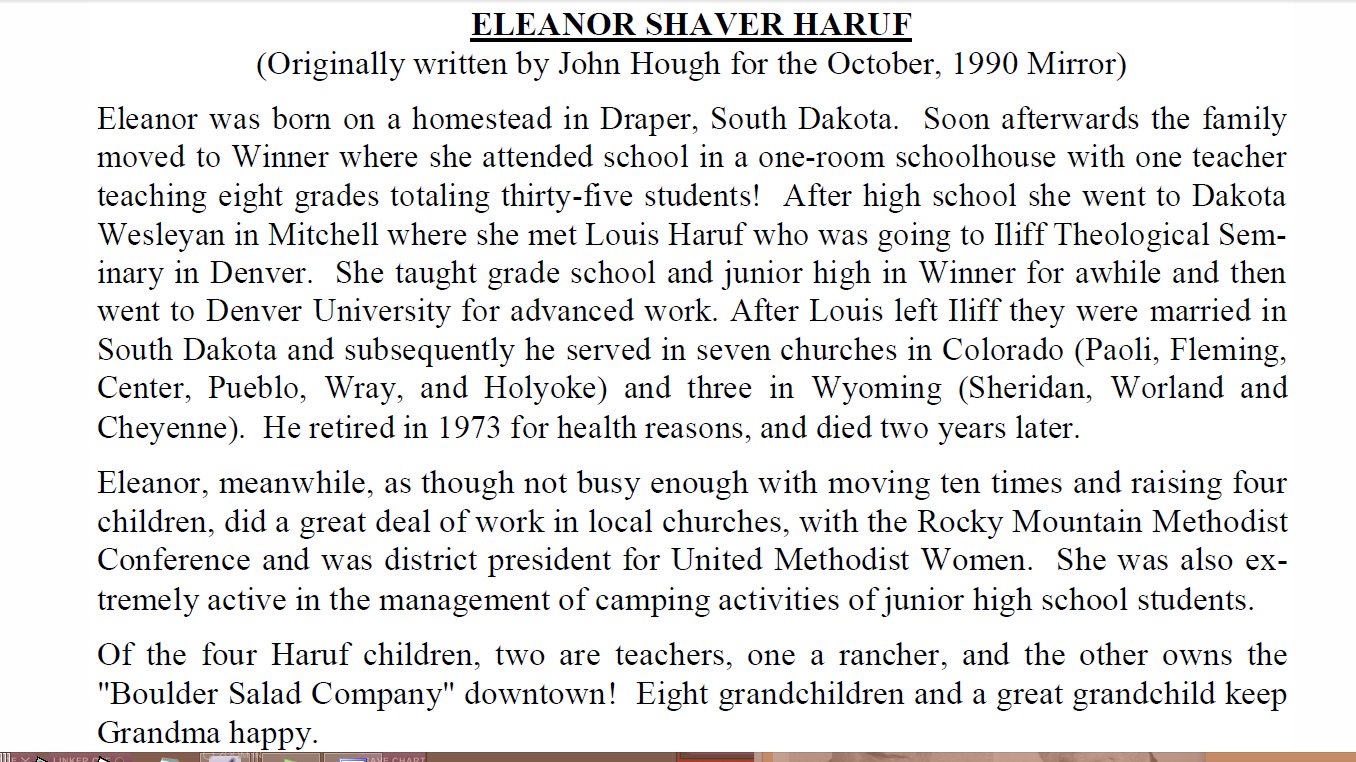

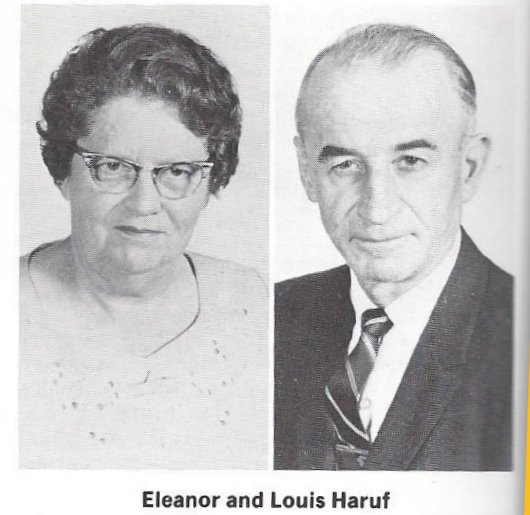

Louis Amos "Hoerauf" was born June 11, 1905 at Grassy Butte, North Dakota, was in Mitchell, South Dakota, in 1930 , and married Eleanor in Winner, Tripp County, South Dakota Sept 24, 1933. His residence was listed as Paoli CALIF, Phillips County, but it was Paoli COLORADO. Eleanor V. Shaver, 25, lived at Winner South Dakota.

|

In 1936 Louis performed the Chester & Hazel Alberts wedding in Fleming.

| I was surprised to know that Kent had taught at Lone Star. Many

years earlier I went to high school at Lone Star after my folks bought

the farm in that area. That was in 1943. And my mother taught 3rd and

4th grades there later. Kent's dad Louis officiated when my husband and

I were married in Wray. Kent was a toddler then. I have enjoyed all of

his books and understand that he had finished another that will be

coming out before long. I am so sorry he couldn't have lived to an old

age.

Lois Blacker |

April 18, 1945 Byron E. Seward was killed in Germany. " In his honor a memorial service will be held at the Laird Methodist church Sunday afternoon at 2 o'clock Rev. Louis Haruf will conduct the service and present the obituary and eulogy and the memorial address."

1952 "The Greeley Methodist church will hear the Rev. Louis Haruf, minister of the church at Holyoke, where he has been for six years. His subject will be The Transforming Love of Christ. Rev. Haruf is a graduate of North Dakota Wesleyan university and Iliff Theological Seminary. "

In 1961, Louis was at Sheridan Wyoming, but he conducted the funeral of Ted O'Neal at the Wages church.

Louis 1905-1973 and Eleanor V. 1908-1992 Haruf are buried in Yuma.

September 17, 1992

|

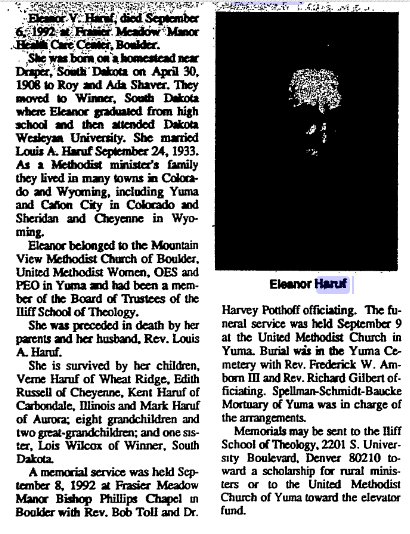

Alan Kent Haruf, 71, of Salida died Nov. 30, 2014, at his home.

He was born Feb. 24, 1943, in Pueblo to the Rev. Louis and Eleanor

Haruf, the third of four children.

He grew up in Holyoke, Yuma, Wray and Cañon City, where he graduated

high school.

Mr. Haruf received a bachelor's degree from Nebraska Wesleyan

University, where he majored in English and history.

From 1965 to 1967 he served in the Peace Corps teaching English in

Turkey.

In 1967 he married Ginger Koon in Lawrence, Kan. They were married

for 25 years.

May 31, 1973 May 31, 1973

August 16, 1973 August 16, 1973

July 3, 1975, Yuma - The Kent Haruf family of Wisconsin arrived recently to spend the summer with Mrs. Eleanor Haruf. They were joined over the week end by the Mark Harufs of Denver.  August 12, 1976 August 12, 1976

Kent and Ginger with their three daughters left Madison, Wisonsin in 1978 and

moved into 608 South Ash in Yuma, working for Bill Wenger at Bill's

Buildings.

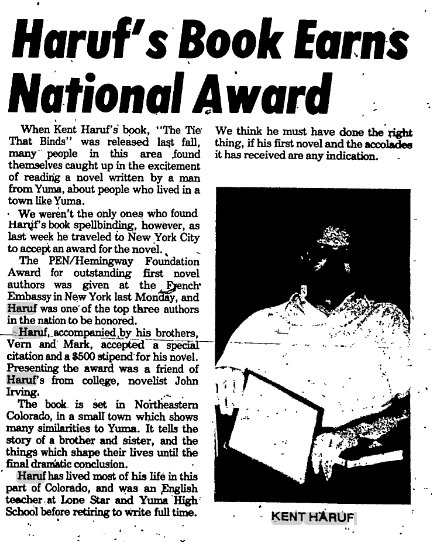

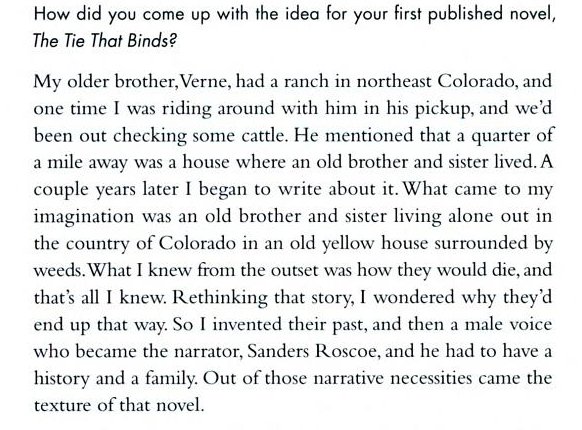

Kent finished "The Tie That Binds" in the basement of the Ash Street house in Yuma.  October 15, 1984 October 15, 1984

Mr. Haruf was a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War.

In June 1983 Ginger was an instructor for Northeastern Junior COllege.  December 15, 1983 December 15, 1983

In May 1985 West Yuma Community Education scheduled a creative writing class, five sessions of two hours each, with college credit from Northeastern Junior Collete. Kent Haruf will be the instructor, and classes will be held at his home, 6035 County Road 41.  May 23, 1985 May 23, 1985

July 1985

Also in July

August 1985  April 1986 April 1986

June 1986

In December 1986 "Kent and Ginger Haruf and family of Lincoln, Nebraska were in Yuma for Thanksgiving at the home of Vern and Shirley Haruf. Kent and Vern's mother Eleanor Haruf of Boulder joined them on Thanksgiving Day. Kent and Ginger rreturned to Lincoln on Monday. Kent didn't live to see Cory Gardner elected to the U.S. Senate in 2014, or Don Brown named Colorado Agriculture Commissioner in 2015. In September 1989 a film by Kent, based on his book "Private Debts, Public Holdings" was shown at the Yuma theatre to wrap up the season of the Colorado Film Network. It won first at the Houston film festival in short films.

Shortly after, the Harufs moved to Iowa, where Mr. Haruf received a

master's degree in creative writing from the Iowa Writers Workshop.

He remarried in 1995 to Cathy Dempsey in Murphysboro, Ill., and they

later moved to Salida.

He taught high school English in Wisconsin and Colorado and held

positions at Nebraska Wesleyan University and Southern Illinois

University in the English and Creative Writing departments.

He retired in 2000 after more than 30 years of teaching.

All his adult life, he pursued his passion for writing, publishing

the following works, among others: "The Tie That Binds," "Where You

Once Belonged," "Plainsong," "Eventide," "Benediction" and "Our

Souls at Night" (to be published in 2015).

Mr. Haruf loved hearing and telling good stories, reading Chekhov,

riding horses, watching the Broncos and spending time with friends

and family.

Survivors include his wife; daughters, Sorel, Whitney and Chaney;

stepchildren, Amy, Joel, Jennifer, Jason and Jessica; brothers, Mark

and Verne; sister, Edith; and grandchildren, Mayla, Lilly, Charlie,

Henry, Sam, Caitlin, Hannah, Destiny and CJ.

----------------------------------------------

Kent Haruf conjured an entire fictional town on the windswept

Colorado Plains - with his eyes wide shut.

Haruf, perhaps Colorado's most celebrated novelist, wrote

Plainsong, Eventide and Benediction by tapping away at an

old-fashioned manual typewriter in his backyard writing shed.

And it was Haruf's style to always type with his eyes closed.

That was his way of allowing his imagination to help him create

quiet, moving stories of the rural townspeople of Holt that

millions of readers found to be universally identifiable.

Haruf, 71, died Sunday morning, November 30, 2014 of lung

disease at his home in Salida, about 150 miles southwest of

Denver.

"Right now, I don't feel like death is right around the corner,"

Haruf said Monday in his final media interview, with Denver

CenterStage. "But if it is, it's a bigger corner than I thought

it was."

Over the past decade, the Denver Center for the Performing Arts

has adapted Haruf's entire Plainsong Trilogy for the live

theatre. Benediction, the third chapter adapted by playwright

Eric Schmiedl, will open on Jan. 30 at the Stage Theatre. And

Haruf's final novel, Our Souls at Night, is scheduled to be

published on June 2.

There has been perhaps no other novelist so keenly in touch with

Colorado's roots.

"It's hard to overestimate Kent Haruf's influence on my life and

on the Theatre Company," said DCPA Producing Artistic Director

Kent Thompson, who has directed all three of Haruf's novels for

the stage. "Kent always wrote with such authenticity,

compassion, honesty and lyricism about life in small-town

America - in his case, set on the Eastern Plains.

"Equally important, Kent wrote about a fundamental question of

our time: Is your family your blood relatives or those who

choose to care and love for you? And how do you build a family

and a community?

Haruf's terminal diagnosis came in February, at the same time a

developmental version of Benediction was being introduced to

Denver audiences as a staged reading at the DCPA's Colorado New

Play Summit. Haruf's pulmonologist didn't give Haruf an exact

timeline for the progression of his disease.

"He told me, 'You may just smolder on for a while," Haruf said

last week, "until you just ... stop smoldering.' "

After initially processing the diagnosis, Haruf said, "it was

important to me to try to make good use of that time. So I went

out to my writing shed every day -- and I wrote.

"I don't want to get too fancy about it, but it was like

something else was working to help me get this done. Call it a

muse or spiritual guidance; I don't know. All I know is that the

trust I had in being able to write every day was helpful."

Haruf set out to write one short chapter every day, and by June,

he had the first draft of Our Souls at Night completed.

"It's the story of an old man and an old woman - something I

know something about," Haruf said. "I'm an old man myself now."

The cast of the 2014 staged reading of "Benediction" at the

Colorado New Play Summit. The fully staged production opens Jan.

30, 2015. Photo by John Moore.

Benediction, too, is about a dying old man, but one very unlike

Haruf. The lead character of Dad Lewis is dying with powerful,

profound regrets about his parenting that are as incurable as

his disease.

"That idea of people dying with regrets that cannot be smoothed

over … that's a very interesting and powerful theme for me,"

said Haruf, who died happily married to his wife, Cathy, and has

been constantly surrounded, he said, in the love of his three

daughters, three step-daughters and two step-sons. Very un-Dad

Lewis-like.

Haruf said he could not be happier that DCPA actor Mike Hartman

has starred in each of the three stage adaptations of his plays,

including Benediction. Hartman said he recently caught himself

"near tears five or six times" just while the reading Schmiedl's

latest Benediction script.

"Kent writes these characters who are so earth-bound," Hartman

said. "Their feet are just so well-planted. They are so

dependable and so unyielding in principle and in the direction

that they are heading."

Hartman, who comes from a rural farming background himself,

feels like he knows the people of Holt intimately, and their

simplicity toward life.

"They are not by any means simple-minded, Hartman said, "but

their lives are not as complex as we get sometimes in the city."

Haruf was born Feb. 24, 1943, in Pueblo, the son of a Methodist

minister, and graduated from Nebraska Weslyan University. He

began writing fiction while in the Peace Corps in Turkey. He

studied fiction writing in grad school at the Writers Workshop

at the University of Iowa. He spent 30 years teaching English

and writing.

Plainsong was a national bestseller in 1999 and won awards from

the New Yorker and Los Angeles Times, and was a finalist for the

National Book Award. Eventide (2004), Haruf's second national

bestseller, was named Notable Book of the Year by several

newspapers, including The Denver Post. His other published

novels include The Tie That Binds (1984), a finalist for the

Pen/Hemingway Award; and Where You Once Belonged (1990), winner

of the Maria Thomas Award in Fiction. Haruf's short fiction has

been included in the Best American Short Stories anthology.

As the end of his life approached, Haruf made a point to begin

each writing day by reading one of three authors – Ernest

Hemingway, William Faulkner or Anton Chekhov.

"Every morning I read something from one of those writers, just

to remind myself of what a sentence can be," Haruf said. "I just

don't have time to be reading something that is not of the

highest quality."

If you want to be a writer, Haruf advised, "I think you have to

learn to read like a writer reads. That is, you are not reading

for entertainment anymore. And you are not really even reading

to see how a story plays out. What you are doing is reading to

discover how somebody else has successfully done something on

the page."

Thompson says he finds it "Haruf-ian" that his mother-in-law,

JoAnn McCall, was the one to first introduce him to Haruf's

writing.

"She gave me a hardback copy of Plainsong," said Thompson, who

was born in Jackson, Miss. "She and my father-in-law, Don

McCall, had grown up in the Eastern Plains of Colorado with the

Haruf brothers, with childhoods and lives interwoven.

"When my wife, Kathleen McCall, and I first met with Kent and

Cathy Haruf -- note the first names -- to discuss adapting

Plainsong to the stage, it felt like a project brought about by

a higher force - fate, faith or the alignment of the planets.

Eric Schmiedl uncannily found the voice of Haruf's characters

and, together with so many actors, we earned the trust of Haruf.

"The plays that followed, Plainsong and Eventide, were deep

dives into both Colorado and humanity. We will all miss Kent

Haruf terribly. From his insight to his guiding hand in

rehearsals, we will never forget this wise friend and brilliant

novelist."

Haruf just contributed an autobiographical essay called The

Making of a Writer to the new issue of the literary magazine

Granta. It begins in 1943 with his birth with a cleft lip, which

was only partially corrected by surgery: "The surgeon was

supposed to do more work on my lip and nose, but he died in a

plane crash and my parents took that as a sign of God's will,

and so nothing more was done," Haruf wrote in the essay.

Many decades later, the lip still was a source of great

embarrassment to Haruf.

"But the truth is, I have come to think ... that perhaps those

years of unhappiness and isolation and living inwardly to myself

have helped me to be more aware of others and to pay closer

attention to what others around me are feeling," he wrote.

Of that essay, Haruf told Denver CenterStage last week, "I tell

how I think I became a writer. I think it suggests some things

that might live on past my own physical being.

"I do want to be remembered as someone who was loving and

compassionate toward other people. And the older I have gotten,

and the closer to death I have gotten, people have grown more

dear to me. So now I want to be completely present when I am

with anybody. I can't say that has always been true. It hasn't

been.

"As a writer, I want to be thought of as somebody who had a very

small talent, but worked as best he could at using that talent.

I want to think that I have written as close to the bone as I

could. By that I mean that I was trying to get down to the

fundamental, irreducible structure of life, and of our lives

with one another."

When Benediction opens on Jan. 30, Haruf said he hopes

audiences leave the Plainsong Trilogy behind having seen a

sweeping portrayal of life as it is.

"In one house, an old man is dying without solving all of his

problems, or being able to end his regrets," he said. "But in

the very next house, there is this 8-year-old girl who is the

representative of hope and promise and youth and joy. What I am

wanting people to feel is that the beginning and the ending in

all of our lives are set side by side. They are not distinct

from one another.

"They are joined as neighbors."

John Moore was named one of the 12 most influential theater

critics in the U.S by American Theatre Magazine in 2011. He has

since taken a groundbreaking position as the Denver Center's

Senior Arts Journalist.

The family of Kent Haruf joined the DCPA Theatre Company family

in February for the Colorado New Play Summit staged reading of

"Benediction." Haruf did not attend because he had just been

given a terminal diagnosis for lung disease. Photo by John

Moore.

Director Kent Thompson, playwright Eric Schmiedl and Dramaturg

Allison Horsley at the 2014 staged reading of "Benediction." The

fully staged production opens Jan. 30, 2015.

|

|

Complete transcript of DCPA Senior Arts Journalist John Moore's

interview with author Kent Haruf conducted on Nov. 24, 2014:

John Moore: Word is you have a new book in the works.

Kent Haruf: I do. At the beginning of May, I started to go out to my

writer's shed outside the house, and by the middle of June, I had

written the first draft of a new novel. Since then I have been

reworking it. (My wife) Cathy has typed it into the computer about

five times now, and my editor at Knopf has edited it. I'll get it

back from the copy editor next week, and the book will be published

on June 2.

John Moore: Do you have a title?

Kent Haruf: Our Souls at Night. You make whatever you want to of

that.

John Moore: I'll have to contemplate that for a bit. Is this novel

a departure for you?

Kent Haruf: It is and it isn't. It's set in Holt; my usual place.

It's the story of an old man and an old woman - something I know

something about. I'm an old man myself now.

John Moore: So does this mean we are going to have a fourth chapter

in the Plainsong Trilogy?

Kent Haruf: Well, we'd have to come up with a new word for it: A

quad-something. But really, no. I think this is completely separate.

It has no connection with the previous books. These are entirely

different characters. It goes off on a different tangent. It is set

in absolutely contemporary times. And to me it has a different tone

and suggestiveness to it.

John Moore: Can you say anything more about the story?

Kent Haruf: Well, I don't like to give it away but it's all set in

2014. And I will tell you there is a reference to the play

Benediction in this new book. It's something these two old people

have a little comment about.

John Moore: That's part of the fun of reading of your stories. Even

in Benediction, which features all new characters, there are those

small references that reward those people who have been with you

from the beginning.

Kent Haruf: It does. And it was a chance for me to have a little

fun. Exactly as you say, people who know these other stories will

immediately recognize what I am talking about.

John Moore: But it's still in Holt?

Kent Haruf: It is. But I will tell you, too, that I hear from

people in Yuma, and it's always a little annoying to me that people

think these are Yuma stories. They're not. I chose the look of that

country as a specific place that I knew very well, and that I could

use as the background setting for the stories I wanted to tell. But

if you think about it, these stories could happen essentially

anywhere. I mean, old men are dying everywhere. And people gather

around and them take care of them. There are lonely old men

everywhere who might very improbably take in somebody to enlarge

their lives and do a good turn.

John Moore: I'm fascinated that you managed to make this happen

while you have been undergoing this medical battle for the past

year. After you got your diagnosis, why was it so important for you

to get this story written?

Kent Haruf: That's a good question. You know, I was doing worse in

February and March, just after we got the news that this lung

disease I've got is incurable and non-reversible. I felt sick and

very downhearted spiritually and mentally. And then in April, I

began to feel a little better, and I thought, 'Well, I don't want to

just sit around waiting.' So I thought I would write some short

stories … but they didn't go anywhere. And then the idea for this

novel came to me.

John Moore: How did you set about to writing it?

Kent Haruf: The idea for the book has been floating around in my

mind for quite a while. Now that I know I have, you know -- a

limited time -- it was important to me to try to make good use of

that time. So I went out there every day. Typically, I have always

had a story pretty well plotted out before I start writing. This

time I knew generally where the story was going, but I didn't know

very many of the details. So as it happened, I went out every day

trusting myself to be able to add to the story each day. So I

essentially wrote a new short chapter of the book every day. I've

never had that experience before. I don't want to get too fancy

about it, but it was like something else was working to help me get

this done. Call it a muse or spiritual guidance, I don't know. All I

know is that the trust I had in being able to write every day was

helpful. I'll tell you, one of my new heroes is Ulysses S. Grant.

You may know that besides being the Northern general who finally

pushed the war to its conclusion, he was also a very bad president.

There was a lot of corruption in his administration. He also smoked

eight or 10 cigars every day. And as he was dying of throat cancer,

he wanted to leave some money for his wife and children. So he began

to write his memoirs. There are pictures of him all wrapped up in

blankets sitting there writing out on the veranda. And he got them

finished, despite his cancer. I think he died two or three days

afterward. Mark Twain had a publishing house then, and he published

Grant's memoirs. It became a national best-seller. So his efforts to

help provide for his wife despite his condition seems to me to be

maybe the bravest thing he ever did. Maybe even more so than

anything he did on the battlefield. So that idea of trying to leave

something was part of what was in my mind.

John Moore: When you get that kind of diagnosis, I imagine you have

one of two choices. You can just sit down and say, 'OK, it's over

for me.' Or you can do what you did, which is to say, 'I am going to

get up every day, and I am going to write.' I know you don't want to

get metaphysical about, but deciding to get up out of bed and march

out to your shed and write -- that had to have come from somewhere.

Kent Haruf: It was metaphysical, and I don't feel apologetic about

that. It's the way it was. At this point in my life, I have been

trying to write fiction for 40 years. So part of what you draw upon

is your experience, and the skill you have accumulated. And again,

it's set in Holt, so I didn't have to invent a new place. It was all

there for me. In some ways it felt as if that was what was keeping

me alive. It was something significant for me to get up for every

day. And then as it turns out, it was a great pleasure for Cathy and

me.

John Moore: Help me to picture this writing shed of yours.

Kent Haruf: When we left our cabin up in the mountains, I had a guy

bring it down and park it in the back of our house in the town of

Salida, out there next to the alley. It's just like a tool shed, but

Cathy and I have converted it into a writing shed, so it has

insulation inside and a big desk. You know, I write on a manual

typewriter, so it's a perfect space for me. Very private. Very

quiet.

John Moore: Does it get cold?

Kent Haruf: Well, I have a heater out here that's plugged into the

house with an extension cord.

John Moore: Tell me about writing on a manual typewriter. My mom

and dad were both writers, too, and my dad decided to retire from

The Denver Post rather than give up his old Royal typewriter for a

new portable computer.

Kent Haruf: It's always worked for me. And then Cathy types them

into the computer.

John Moore: I have a theory that authors who wrote on typewriters

had to know pretty much what they were going to write from the time

they sat down to type, because they had no delete key. Contemporary

playwrights, specifically, often seem to be working it out as they

go along on the computer, and I think it shows in the storytelling.

Kent Haruf: Well, that's true to a extent. I always know the first

sentence or two before I sit down. Once I have typed that, it's a

springboard to the rest of it. But the first sentence has to be one

that sets the right tone for the story. There is a kind of momentum

that first sentence or two generate, and that carries me through.

And I don't know if you know this, but I type all of this with my

eyes shut. And I never allow myself to get up from the typewriter

until I have written that whole scene. And it's all single-spaced on

one sheet of paper. It works well for me. I have just accepted that

as my own discipline, and my own rule. So I am not going to answer

the phone or do anything else but work. It doesn't take that long to

type up one sheet of paper, but it's all intense concentration, so I

am unaware of anything else except for that effort.

John Moore: Well you have proven over your entire career, and

specifically over the past year, just how disciplined you must be

about your writing routine. The playwright Matthew Lopez, who wrote

The Legend of Georgia McBride and is spending the year in residence

at the DCPA, says the difference between a writer and a hobbyist is

the difference between one who writes and one who just talks about

writing. He said you have to treat it like a daily job. What is your

advice to aspiring writers?

Kent Haruf: The obvious thing is to read, read, read, read, read.

Then write, write, write. There is no way around it. You have to do

both of those things. But in terms of reading, I think you have to

learn to read like a writer reads. That is, you are not reading for

entertainment anymore. And you are not really even reading to see

how a story plays out. What you are doing is reading to discover how

somebody else has successfully done something on the page. So you

are paying very close attention to what works, and what doesn't

work. And once you get to be a skillful reader, there is a different

kind of pleasure in reading someone great. So no, I really don't

read much of anything except I go back over and over to Faulkner and

Hemingway and, particularly, Chekhov. I never get tired of reading

them. Every morning before I write, I read something from one of

those writers, just to remind myself of what a sentence can be. I

read every day. If I don't, I feel it's been an unsatisfactory day.

I just don't have time to read something that is not of the highest

quality.

John Moore: So are you reading anything other than those three

authors?

Kent Haruf: Oh yes. But what I am mostly reading right now is

spiritual stuff, because I am trying to understand what is going on

with me.

John Moore: You had just gotten your diagnosis when Benediction was

being read at the Colorado New Play Summit last February. Do you

mind my telling people what that exact diagnosis was?

Kent Haruf: I have interstitial lung disease, and the pulmonologist

tells me there is no cure for that. What they prescribe for that is

prednisone. That's a steroid, and it makes you feel somewhat better,

but it doesn't fix anything. There is no reversal, obviously. So I

have tried to concentrate instead upon thinking positively; upon

thinking about things that I am grateful for. I feel enormously

grateful for what I have had in my life. I feel very grateful to

have this time to sort out my thoughts about religion and God and

afterlife. Cathy and I have given ourselves a seminar course in

spiritual thought about death and dying. We've read dozens of books

about it, and I never would have done that had I not been forced to

by these circumstances.

John Moore: If I might, have they told you how much time you should

expect to have?

Kent Haruf: They didn't give me any special number of days or

anything. But one of the pulmonologists said, 'You may just smolder

on for a while … until you stop smoldering.' At the time it seemed

such a crazy figure of speech, but maybe it's more accurate than I

know. I've gone up and down. Right now, I don't feel like death is

right around the corner, but if it is, it's a bigger corner than I

thought it was.

John Moore: You said you never really thought much about death and

dying before your diagnosis. But Benediction seems to be about

exactly that. The journey Dad Lewis is on seems a precursor to what

you are going through now. When you were writing Benediction, you

had not yet been diagnosed. But you were thinking about yourself in

any way?

Kent Haruf: Not really. Well, my own experience had to have some

influence in forming that story. But I have been a hospice

volunteer. My wife is still involved in hospice, and has been for 10

years or more now. So I have been around death, and I have had

thoughts about dying. Writing about a man who was dying was an idea

I was interested in, but I didn't want to do what's always been done

so many times before. There is no question from the opening page of

Benediction that he is dying. So that is not a surprise. It's not a

matter of suspense. What I hope that book is about is how he lives

in his last months and days. The fact that he has these powerful,

profound regrets that he would like to rectify but cannot -- that's

the intent of those scenes at the end, when he is having these

visions of people visiting him and talking to him. He has a vision

of Frank coming back to see him. But even as badly as he wants that

to happen, even in his hallucinatory vision, he cannot realistically

see how he would ever be forgiven by his son for the terrible

mistakes he has made earlier. And so that idea of people dying with

regrets, without things becoming smoothed over; that's a very

interesting and powerful theme for me. The other thing I would say,

of course, is that death draws in people around him -- neighbors and

friends, and of course in a small town it would be common for a

preacher to visit somebody in the church who was dying. So it seemed

natural for me to have those people gather around Dad Lewis as the

center, and the reason for all of them to know each other.

John Moore: Is there anything you have learned over the past year

that might have changed the way you wrote Dad Lewis in Benediction?

Kent Haruf: I think if I were to write that book now, I would write

some things about his physical condition differently. I am finding

this to be pretty physically challenging. I don't know that I

conveyed too much of that in his story. But I didn't want to belabor

that, either, because that gets pretty old to read about.

John Moore: So we know that you created Dad Lewis in your head, and

you made him come to life on those pages, before you got your own

terminal diagnosis. So has Dad Lewis in any way helped you in this

part of your journey?

Kent Haruf: It's a good question, but I am not sure that I would

say he has. As much as I like Dad Lewis -- he's a character I love,

really -- but I don't really identify with him in that way. My

death, in its approach, seems to me to be very individual. At this

point in my life, death seems like the main event, and that's what

I'm concentrated on. So my life has become very narrowly

circumscribed. I don't see very many people. I haven't left the

house in the past two months, so I am probably less social than Dad

Lewis was.

John Moore: But unlike Dad Lewis, you have a large and loving

family, a huge support system, and none of the same regrets.

Kent Haruf: That's exactly right. My children and my stepchildren

have been wonderful, and I have to tell you: I have received

well-wishes from people all over the world. I used to deflect that,

because I didn't want to be egotistical about it. Now I believe

those kinds of things really do have some actual, literal benefit to

people.

John Moore: Oh, absolutely. I think if you have touched someone

with your deeds or words, then giving people the opportunity to tell

you that is a gift you are giving them.

Kent Haruf: I know exactly what you are saying, and it has taken me

awhile to come to that view, John. I have been slow in understanding

that. If somebody gives you something, and you don't receive it, the

gift is not completed in some way. It's like sending a letter that

never gets delivered. I have tried to learn in these last months how

to be receptive. That's not my nature. My nature is to be

self-effacing. But it's not selfishness to accept a gift from

somebody. It's taken me a while to learn that.

John Moore: Can you tell me what it means to you, especially at

this time of your life, that the DCPA Theatre Company has followed

through on its commitment to create and complete this Plainsong

Trilogy for live theatre audiences?

Kent Haruf: Oh, I think it is absolutely wonderful. It is a great

honor to me. It feels as if it ties me into people in Denver and

throughout the state, and I feel a great gratitude about that. I am

always aware of how skillful Kent Thompson and Eric Schmiedl are,

and Mike Hartman. I couldn't be happier that Mike has been cast as

Dad Lewis. They sent us the video of the public reading that was

done at the 2014 Colorado New Play Summit this last February, and

Mike was just superb in that.

John Moore: You've talked very openly about what is next for you

and how you don't know the timing -- but you do know that the time

is going to come. And so I think it's a rare privilege and honor to

ask someone in your situation: How do you want to be remembered?

Kent Haruf: Well, that's a good question. You know, John, I don't

know that I have thought all that much about that. One thing that

springs to mind in the October issue of the Granta literary

magazine, I wrote a piece called The Making of a Writer. You might

be interested in reading that before you write up this piece.

Because in that essay, I tell how I think I became a writer. And I

think it suggests some things that might live on past my own

physical being. I do want to be remembered as someone who was

loving and compassionate toward other people. And the older I have

gotten, and the closer to death I have gotten, people have grown

more and more dear to me. So that now I want to be completely

present when I am with anybody. I can't say that has always been

true. It hasn't been. And as a writer, I want to be thought of as

somebody who had a very small talent but worked as best he could at

using that talent. I want to think that I have written as close to

the bone as I could. By that I mean that I was trying to get down to

the fundamental, irreducible structure of life, and of our lives

with one another.

John Moore: When Benediction opens in January, and people leave not

only this story but this trilogy of stories behind, what do you hope

they most will have gotten out of the lessons learned from the time

they have spent in Holt?

Kent Haruf: What I hope is that they will see that this is a

portrayal of life as it is. That in one house, an old man is dying

without solving all of his problems, or being able to end his

regrets. But in the very next house, there is this 8-year-old girl

who is the representative of hope and promise and youth and joy. And

so what I am wanting people to feel is that the beginning and the

ending in all of our lives are set side-by-side. They are not

distinct from one another. They are joined as neighbors.

John Moore: With the opening of Benediction coming up on Jan. 30, a

lot of people want to know if you are going to be well enough to see

it.

Kent Haruf: Well, I am going to make every effort, assuming I am

still alive. We've bought a lot of tickets for family, and my agent

and editor will come out from New York. I am going to go to Denver

on the 5th of February. I am going to need a wheelchair, and we'll

stay at the Curtis Hotel. That will be handy. Someone will have to

push me over there. I don't know if I'll still be around then or

not, but if I am, I am sure going to work hard to be there.

John Moore: I am going to go with yes, you are going to be there.

Kent Haruf: Thanks, John. I'll count on that.

Courtesy of the Colorado Independent Denver Post

With the death of novelist Kent Haruf, Colorado has lost one if its

celebrated native sons, its astute and wise observer of rural life

and community on Colorado's Eastern Plains.

The prize-winning author of the acclaimed trilogy "Plainsong,"

"Eventide" and 2013's "Benediction" - all set in the fictional town

of Holt, Colo. - died Sunday at the age of 71. The cause was

interstitial lung disease. He is survived by his wife, Cathy, and

three daughters. Additional survivors are three stepdaughters and

two stepsons.

"He really was a giant," Gov. John Hickenlooper said Monday of the

writer, who was born in Pueblo in 1943.

Among Haruf's many literary honors were the prestigious Whiting

Foundation Award for his first novel, "The Tie That Binds"; the

Center of the American West's Wallace Stegner Award, given to those

who've "made a sustained contribution to the cultural identity of

the West through literature, art, history, lore, or an understanding

of the West"; and a special citation from the PEN/Hemingway

Foundation.

Winner of the 2000 Mountains and Plains Booksellers Award,

"Plainsong" was a finalist for the National Book Award. And in 2008,

the Denver Center mounted the world premiere adaptation of

"Plainsong." It was followed by the premiere of "Eventide," in 2010.

"I thought 'Plainsong' and 'Eventide' were two of the best books

ever written about Colorado," Hickenlooper said.

Haruf's graceful, grounded portrait of a rural community was on

then-Mayor Hickenlooper's short list when he launched One Book/One

Denver in 2004. "I came very close to picking 'Plainsong,' "

recalled Hickenlooper.

"Except there was one kind of dicey scene where teenagers were

having sex and a 10-year-old watches them through a knothole in this

shack. For something we were just starting, we thought it was too

racy."

"Like a fool, I told Kent this. I'm not sure he ever really forgave

me," Hickenlooper said. "And you know, with a little bit of

distance, he was completely right. It was so integral to the story,

so maturely done. In no way was it lascivious. I still feel guilty

about it."

A rare relationship Actor Mike Hartman, in a phone interview from

New York, referred to Haruf as his "BS meter." The Denver Center

Theatre Company member starred in "Plainsong" and "Eventide." In

January, he will portray Dad Lewis, the dying protagonist in

"Benediction."

"He would stand or sit next to Kent Thompson (artistic director of

the Denver Center company) or the playwright in rehearsal and he'd

be watching things," Hartman recalled. "When he didn't like what he

saw, you'd see him move around or get agitated. His face would screw

up."

In 2006, Thompson and playwright Eric Schmiedl began working with

Haruf to bring his trilogy to the stage.

"It was really one of those relationships that are rare," Thompson

said. "It's a profound loss on both the friendship and artistic

level. We did lose a muse."

The relationship forged between the Denver Center and Haruf was, to

borrow a notion, "kismet."

A year or two before coming to the Denver Center from the Alabama

Shakespeare Festival, Thompson had been given a copy of "Plainsong"

by his in-laws.

"The novel was spectacularly good," he recalled thinking. But at the

time it didn't make sense for what Thompson was doing in Alabama.

"Within a year or two, I was at the Denver Center."

And he "brokered the marriage" between the novelist and playwright

Schmiedl.

"These can be quirky relationships when you're working together,

adapting something from another art form and transferring it to a

totally different experience," said Schmiedl.

"Kent was just so generous about the whole process. He wanted to be

intimately involved, but not in a controlling fashion. He certainly

had a strong view about the work and the characters and the

authenticity of story, but he was curious. We talked a lot about how

challenging it was as a fiction writer to sit back and kind of trust

that the artists working on the show are going to have the best

interests of the novel at heart," said Schmiedl. "It was such an

asset for us to have the source of the material in the rehearsal

hall with us."

In 2015, Alfred A. Knopf will publish Haruf's sixth and final novel,

"Our Souls at Night." Haruf told the Denver Center's John Moore in

what was the author's final interview that it, too, is set in Holt.

Moore asked if the trilogy was about to get a new chapter.

"Well, we'd have to come up with a new word for it: a

quad-something. But really, no. I think this is completely

separate," Haruf replied. He then teased: "I will tell you there is

a reference to the play 'Benediction' in this new book. It's

something these two old people have a little comment about."

Thanks to Lisa Stevens and the Denver Post |

By Jennifer Maloney May 14, 2015 Kent Haruf knew he was dying, but he felt well enough to attempt one more project. It was May of last year, and Mr. Haruf, the best-selling novelist known for his quiet chronicles of small-town Colorado life, had been diagnosed with an incurable lung disease. "I have an idea," he said to his wife, Cathy Haruf. "I'm going to write a book about us." He stretched the long tube of his oxygen tank out the back door of their bungalow to his writing shed, and began to type. Normally, it took him six years or more to write a novel. But in a rush of creative energy, he wrote a chapter a day. Roughly 45 days later, he had finished a draft of his final novel, "Our Souls at Night." Mr. Haruf died at home in Salida, Colo., on Nov. 30. He was 71 years old. In the months and even days before he died, the author worked with his wife and his editor, Gary Fisketjon, to finish it. His publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, will release the book on May 28 with a first print run of 35,000. A short, spare and moving novel about a man and a woman who find love late in life, "Our Souls at Night" is already creating a stir. The novel has been selected by the American Booksellers Association as the No. 1 Indie Next Pick for June. Discussions are under way for a film adaptation, according to Mr. Haruf's agent, Nancy Stauffer. "Knowing that there will be no more," readers may find this book even more powerful than Mr. Haruf's previous novels, said Cathy Langer, lead buyer at the Tattered Cover Book Store in Denver. "Plainsong," his most famous book, has sold more than one million copies in the U.S. "Plainsong," in which two old, cantankerous bachelor farmer brothers take in a pregnant teenager, was the first in a trilogy, all set in the fictional town of Holt, Colo. The new novel is set in the same town, but is separate from the trilogy. "It has all of those Haruf-like things-the community, the forging of relationships," Mr. Fisketjon said. "But there is something about this book that seems to me completely different... The simplicity of it, the directness of it. The get-to-it-ness of it. The opening is like, Wow." The book begins with a proposition: A 70-year-old widow named Addie Moore knocks on the door of a longtime neighbor and asks if he would like to come to her house at night to lie in bed-not for sex, but to talk and fall asleep together. "I'm talking about getting through the night," she says. "And lying warm in bed, companionably. Lying down in bed together and you staying the night. The nights are the worst. Don't you think?" "Yes. I think so," he says. Alan Kent Haruf was born in 1943 in the steel-mill town of Pueblo, Colo. His father was a Methodist preacher. That summer, his family moved onto the Eastern Plains of Colorado, where they lived in three different towns over the next 12 years. This was the landscape where he would set his novels. He attended high school in Cañon City, Colo., where, freshman year, he met Cathy Shattuck. They lived on the same street. (Her father was an Episcopal priest.) The two became close friends, playing in the band together and commiserating over girlfriends and boyfriends. They went on double dates together but never dated. At Nebraska Wesleyan University in Lincoln, Mr. Haruf discovered Faulkner and Hemingway, and decided to become an English teacher. He began to write short stories while volunteering with the Peace Corps in Turkey, and applied to the Iowa Writers' Workshop. He was rejected. He married in 1967 and continued to write, applying to the workshop again in 1971. This time, he moved his wife and baby daughter to Iowa before the school finally admitted him. He spent the next 11 years trying to get published. He taught high-school English in Colorado and Wisconsin, and wrote during the summers. "The Tie That Binds," his first published novel, was released in 1984 when he was 41. In 1991, he rekindled his friendship with Cathy Shattuck (by then Cathy Dempsey) at their 30th high-school reunion. Both of them were married. She had five children. He had three. She was a special-education teacher in Virginia, working with physically disabled students. He began to write "Plainsong" soon after that, modeling one of the characters, a teacher named Maggie Jones, after her. Within a few years, both of their marriages had ended. Their relationship began long-distance, with long talks on the phone. In 1995, she joined him in Illinois, where he was teaching in the MFA program at Southern Illinois University. They were married that year. "Plainsong" was published in 1999. It was a runaway best seller, and a finalist for the National Book Award. "From simple elements, Haruf achieves a novel of wisdom and grace–a narrative that builds in strength and feeling until, as in a choral chant, the voices in the book surround, transport, and lift the reader off the ground," the National Book Award citation said. The success of "Plainsong" meant that he could now write full-time. Kent and Cathy Haruf built a cabin in the mountains near Salida, Colo., about 60 miles west of the town where they attended high school. She got a part-time job as a hospice volunteer coordinator, so she could travel with him on book tours. "They were just so in love," the author's sister-in-law Kathy Haruf said. "You could feel it when you were with them." In the woods by their cabin, they adapted a tool shed-insulated, with a space heater, desk, typewriter and bookshelf. Every morning at 9, rain, shine or snow, Mr. Haruf would head out there. He would read a passage from one of his favorite authors-Hemingway, Faulkner or Chekhov-"just to remind myself of what a sentence can be," he said in an interview with John Moore, a journalist with the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, last November. Then he would roll an old, yellowed sheet of paper into his Royal typewriter, pull a stocking cap down over his eyes, and type blind, his head sinking toward the keys. He would write one scene, with no punctuation or paragraph breaks, filling a page with single-spaced text. He wouldn't allow himself to get up until he had finished the scene. When he was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease in February 2014, he felt "sick and very downhearted spiritually and mentally," Mr. Haruf said in the same interview, six days before he died. "And then in April, I began to feel a little better, and I thought, ‘Well, I don't want to just sit around waiting.'" After he was diagnosed with an incurable lung disease, author Kent Haruf and his wife Cathy formed a two-person book club of sorts. Mr. Haruf described it, in an interview with the Denver Performing Arts Center, as "a seminar course in spiritual thought about death and dying." The two of them, each morning, read and discussed dozens of books about death and spirituality. In "Our Souls at Night," Mr. Haruf's final novel, Addie asks Louis: "Aren't you afraid of death?" "Not like I was," he replies. "I've come to believe in some kind of afterlife. A return to our true selves, a spirit self. We're just in this physical body till we go back to spirit." Below, some of the books the Harufs read together: "On Death and Dying," by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross "Dying To Be Me," by Anita Moorjani "Wishes Fulfilled," by Wayne Dyer "Many Lives, Many Masters," by Brian L. Weiss "Ask and It Is Given," by Esther and Jerry Hicks "On Life after Death," by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross "Messages From the Masters," by Brian Weiss "Only Love Is Real," by Brian Weiss "Sacred Contracts," by Caroline Myss . He tried to write some short stories, but didn't get anywhere, and then the idea came to him for a novel. "In some ways it felt as if that was what was keeping me alive," he said. "It was something significant for me to get up for every day." He asked his wife not to tell anyone he was writing a book. He wanted it to be surprise. He started on May 1. By mid-June, he had finished the first draft. He revised and retyped it, and one afternoon in early August, Cathy Haruf said, "Well, are you ready for me to read it?" "Yes, I think so," he said. She retrieved the manuscript from the shed, sat down and read it all at once. It was not a literal retelling of their marriage. But there they were, recast as Addie Moore and Louis Waters. When she read Addie's fearless proposition, she thought, "Oh yeah, he knows that I would be the kind to do something like that," said Ms. Haruf, 71. The Harufs' favorite time together was lying in bed at night, talking. "It's our love story," she said. "We would lie there and hold hands and talk. There wasn't anything we never discussed." In the novel, Addie and Louis slowly reveal themselves, and their life stories, as they lie in bed talking. Their connection deepens when Addie's grandson Jamie comes to stay with her, and it's tested when neighbors and loved ones voice objections to the relationship. Woven through the book are details from Mr. Haruf's life, including subtle nods to his children. "There we are in these pages," his daughter Sorel Haruf said. "It's a final blessing to all of us." Cathy Haruf typed the draft on their computer, and updated it as her husband made revisions. She sat next to him in bed, with a pad and pen, making a timeline of the characters, to make sure the fictional dates lined up. They brainstormed titles together. (They rejected: "Till We Meet Again," "Night Time," and "Cedar Street.") And they debated the ending. Ms. Haruf objected to the ending of his first draft, which she argued was out of character for Addie. "Addie would not do this!" she said. He rewrote it. On Sept. 22, he emailed the manuscript to Mr. Fisketjon. "Here's a little surprise for you," he wrote. "I said, 'What the f---!'" Mr. Fisketjon recalled. "Shock and awe." Mr. Haruf's doctors hadn't told him how long he might live. Mr. Fisketjon, knowing that they may not have much time, dropped everything to edit it. Knopf art director Carol Devine Carson, who designed the jackets for the "Plainsong" trilogy, took up the project right away. The trilogy's covers had all depicted landscapes. For this, she proposed a more intimate image: the silhouette of a wooden headboard against a wall. Mr. Haruf loved it. The book went through a round of editing. Then it went to a copy editor. Knopf express-mailed a copy-edited manuscript to the Harufs on Nov. 25. Mr. Haruf was very weak. He told his wife she would have to give it the final read. On the night of Nov. 29, Kent and Cathy Haruf lay in bed-she in their queen bed and he in a hospital bed alongside it. They held hands, talking quietly, then fell asleep. When she woke in the morning, he was gone. |

Thanks to the Denver magazine "5280" written in the summer of 2015 Cathy Haruf returns from the snow-covered backyard of her Salida home carrying a small box of papers. It's late in the morning on Wednesday, February 25, the day after what would have been her late husband's 72nd birthday. She sits across from me in an old brown rocking chair in the corner of the living room and rests the box on her lap. The chair creaks as it sways, and Cathy settles into place. On the opposite side of the room, displayed on a cabinet, there is a framed picture of Kent. After a quiet moment, Cathy begins to sort through the contents of the box. There are handwritten letters, a spiral-bound journal, and a stack of manila papers. The sheets make up the manuscript of her husband's final novel, Our Souls at Night, which he worked on until the day he died, November 30, 2014. The pages are filled mostly with single blocks of typed text, and there are pencil marks and crossed-out words and passages and notes in the margins. For months Cathy has been mailing boxes of these papers to the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, where they will be preserved and catalogued alongside work by the likes of Shakespeare, Galileo, Henry David Thoreau, and Jack London. This is one of the last boxes she will send. Kent Haruf is widely considered Colorado's finest novelist and one of America's most important contemporary literary voices. Critics have written that his sentences "have the elegance of Hemingway's early work" and that he "may be the most muted master in American fiction." His books have been translated into more than a half-dozen languages. His third novel, Plainsong, was a best-seller and was nominated for a National Book Award in 1999, one of the highest honors in American letters. The Denver Center for the Performing Arts has adapted three of Kent's books for the stage, most recently his fifth novel, Benediction, which in many ways foreshadowed his own death. And an award-winning director has already expressed interest in purchasing the film rights to Our Souls at Night, published last month. In the bright living room, Cathy hands me one of the manila sheets: page 16 of the first draft of Kent's last book. She then places the box on the floor in front of us, and we look through Kent's papers together. A few minutes later, Cathy asks if I'd like to see the shed behind the house where Kent wrote Our Souls at Night and his previous two novels, Eventide and Benediction. With a pencil, she scribbles a three-digit sequence, the code for the combination lock on the shed, on a scrap of paper. Instead of accompanying me outside, Cathy hands me the paper and suggests, without hesitation, that I go alone. The structure is just beyond the fenceline: a small brown shed with a fresh blanket of snow clinging to the roof. It looks like the kind of thing you'd pick up at Home Depot. This was Kent's sanctuary, the place where he daydreamed into existence a world that showed in all its simplicity that life is anything but plain. I walk around to the front, dial the combination, remove the padlock, and open the door. Even now there are not many trees here, although people in towns like Holt have full-grown trees that were planted by early residents sixty and seventy years ago in backyards and along the streets-elm and evergreen and cottonwood and ash, and every once in a while a stunted maple that somebody stuck in the ground with more hope for it than real experience of this area would ever have allowed. -THE TIE THAT BINDS The drive from Denver to Salida-from the busy city highways to the quiet small-town streets tucked between 14,000-foot peaks and near a calm stretch of the Arkansas River-takes three hours, winding, and climbing, and dipping through the mountains along U.S. 285. I made the trip multiple times last summer to speak with Kent, and on each occasion we visited for hours in his home. When I first reached out to Kent, I didn't know he was working on a new book or that he had seen very few visitors during the previous months. I'd recently read Plainsong and was moved by the rhythm and soulfulness of the story and of his writing, the way one might feel a connection to a beautiful piece of music or the brushstrokes of a brilliant painter. I felt compelled to reach out to the man behind the novel. I wanted to talk with him-and to listen. A publicist at Random House connected Kent and me via email; we exchanged a few messages, and he agreed to meet with me at his house in Salida on June 23. Cathy later told me that she was a bit surprised when Kent said there was "a young man coming down from Denver to visit." I arrived at the Harufs' home around 4:30 p.m. that afternoon in June. Kent answered the door. He looked more frail than in the pictures on his book jackets, and there were rubber tubes tucked behind his ears and up into his nostrils. The tubing trailed behind him several dozen feet back through the entryway and across the kitchen floor and into the living room, until they disappeared under a closet door. Kent invited me in. We sat in the living room. He was winded from walking to the front door and back to his chair, the old rocker. We spoke for a long time, and like Kent's prose, his voice was soft and measured. On my drive through the mountains several hours earlier, I listened to an interview with New Yorker writer Peter Hessler, who has spent years reporting from China. In the interview, Hessler explained that one of his strategies had always been to leave the big cities and travel to small towns. "Everything is more obvious in a smaller place," Hessler said in the interview. "It stands out more." Hessler's comments made me think of Kent's novels. All of Kent's books are set on Colorado's Eastern Plains in the fictional town of Holt, which he created and then painstakingly brought to life on the page. Beyond the occasional trip to Denver or the mountains, his characters-Edith Goodnough, Victoria Roubideaux, the McPheron brothers, Dad Lewis-rarely stray far from the edges of town. Kent spent much of his childhood on the High Plains. He was born in the steel-mill town of Pueblo in the winter of 1943. Kent's father was a Methodist preacher, and the family moved often-Kent was an infant when they packed up and left Pueblo and settled on the plains east of Denver. The Haruf family spent the next 12 years in Wray, Holyoke, and Yuma, little towns amid expansive country. As a kid, Kent didn't think much about becoming a writer. In his early years, he remembers being "more or less a happy kid." He also says that during that time, he "learned to live completely inwardly," a sentiment owed to the fact that he was born with a cleft lip. Kent's parents were too poor to afford treatment alone, but local churches helped raise money so the Harufs could send their newborn to Children's Hospital in Denver. Kent remained at the hospital for about a month while doctors did what they could to repair his lip. The surgeon planned to do more work later, but when he died in a plane crash, Kent's parents viewed it as a sign from God to let it be. For more than 15 years, from the time he was 12 until he neared 30, Kent felt an impulse to conceal his face behind his hand, to hide what he considered an embarrassing imperfection. But his thinking changed over time. Later in life, he came to believe the deformity was a gift that had taught him to be more aware of the world around him and of the feelings of others. "Which are good things," Kent has said, "if you are trying to learn to write fiction about characters you care about and love." In his 30s, Kent grew a mustache to cover his lip; he kept it for the rest of his life. Listening to Hessler's interview on that summer day, I wondered if Kent felt about his fiction the way Hessler did about his journalism; that the quiet setting of the plains somehow amplified the emotions and interactions of his characters. "I feel that exactly," Kent told me. It worked just perfectly, he said, to set his novels on the stark landscape of the plains because there was so little to obfuscate the story. Later, he told me, "I love driving around through the plains at night, when you see those yard lights scattered around in the country. It's so beautiful to me. And yet so lonesome.… There's a kind of tension between those two feelings, and I love that." Just once they took another boy with them to the vacant house and the room where it had happened. They wanted to see it again themselves, to walk in it and feel what that would feel like and what it might be to show it to somebody else, and afterward they were sorry they had ever wanted to know or do any of that at all. |

VERNE

In 1952 Verne Haruf, who had played with the Holyoke Dragons a year earlier, was playing for Yuma. He intercepted a pass in the opening quarter and returned it down near the goal line and almost scored which would've put an end to the Dragons' perfect goose egg on the defensive side of the ball. The Dragon defense stood tough and went on to take a 52-0 win from the Indians.

Shirley Parrish was born March 5, 1935 to Clara and Russell Parrish in Yuma, and married Verne in 1957. They lived in Holyoke, Colorado, Thermopolis Wyoming, and Byers Colorado.

Vern Haruf, Wayne Mekelburg and brothers Stan Herman, Roger Herman owned and

operated Mill Iron Diamond Cattle Company, a large diversified agriculture

business. The company farmed both dry and irrigated land, fed custom yearlings

and had a cow-calf operation. They were also involved in a partnership with Mid

5 Feedlot and Yuma Dairy.

In 1979 Jackie Haruf, freshman from Yuma, Colo., daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Verne Haruf, was nominated by the nursing department for Homecoming queen at Garden City, Kansas Community College.

"

Gathering Saturday, May 24, 2014, for the 60th class reunion, members of the Holyoke High School class of 1954 are pictured from left, front row, NELDA Hofmeister O'Neal of Holyoke, Norma Kunkel Warren of Holyoke, Marva Brandt Seymour of Murrysville, Pa., Karen Travis Trumper of Holyoke, teacher Marilyn Ruwaldt Garretson of Haxtun, Bonnie Martin McFadden of Sedgwick, Charlotte Klitz Greene of Sun Lakes, Ariz., Carol Miles Schmidt of Haxtun and NAOMI Neiman Newman of Holyoke; and back row, VERNE HARUF of Yuma, Jim Stenson of Aurora, Bob Schmidt of Sun City, Ariz., Tommy Thompson of Haxtun, Stan Willmon of Holyoke, Jerry Ahnstedt of Longmont and Bob Trumper of Holyoke. Not pictured are Grant Ferguson and Lyle McCormick.

NELDA was the daughter-in-law of Ted O'Neal, for whose 1961 funeral Louis

came from Sheridan Wyoming to conduct. NAOMI NEIMAN grew up two miles

north of the Wages church, and attended it when Louis was preaching there.

-Enterprise photo

EDITH

Edith Haruf Russell graduated from the University of Wyoming - Education- in 1965.

Edith and Bryan Russell were acknowledged in the preface of Plainsong.

Ginger (Virginia) was living in Colorado when her mother died in 2013. Dorothy Virginia "Dottie" (Delhay) Koon, was born Sept. 4, 1919 in Lincoln to Dianah Marie (Staberg) and Alfred Maurice Delhay. She passed away peacefully at home on Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2013. Dottie attended Kindergarten in Waverly and transferred to Havelock when her parents moved to Logan Street. She graduated from Havelock High in the Class of '37, walking to and from 5726 Baldwin when her family moved to University Place her senior year. She attended Nebraska Wesleyan University for one year, intending to become a Physical Education teacher. Plans changed when she met her future husband, Gene, while playing softball for Martin's Blackbirds (#4) at Municipal Ball Park. This led to their three year engagement and future marriage on June 23, 1940, in her parents' home. For their honeymoon, Dot and Gene traveled to the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, Cal. to watch the Huskers win! Dottie also played forward (#44) for the Lincoln Engineering basketball team sponsored by husband, Gene. In 1952 they moved to the home they built together at 5721 St. Paul. They joined First United Methodist Church, where Dottie and their three daughters were all baptized. Dottie was president of Mother's Club at Northeast Child Center, where her children started school. She would continue to mother many of the friends of her girls, as they could always find an afternoon snack at "Mom" Dot's table at 5803 Baldwin Avenue. The two story white house would continue to be home until 1965 when the family moved to Tempe, Ariz. Dottie worked at a family owned business, Fashion Bootery, continuing to make friends with neighbors and co-workers. Returning to Lincoln in 1989 brought Dottie great joy. At this time, Gene retired and they moved to 3810 Everett, where she stepped into her home town life, becoming part of the Wesleyan Women's Education Council. First United Methodist Women's (UMW) organization presented her with the Dedicated Light Honor for her years of service to her church. She also served on the Bryan Hospital board. When she was 80 years old, she was honored by UNL Girl's Softball team by being asked to throw out the first pitch of the season. In their last years, Gene and Dottie moved in with middle daughter, Jan. After Gene's death in 2006, she continued her love of ball playing days by reading about and watching all sports events from home. Her favorite color was Husker red, and the rose her favorite flower. She loved being outdoors and especially sitting on the sunny deck. Her joys included eating apples and home grown tomatoes, sweeping driveways and sidewalks, and watching the birds with her loyal canine companion, Georgie, by her side. Her competitive spirit came through in her playing cribbage with family and friends. She was someone who made others feel good just by being around her. She made the world a better place. Dottie is preceded in death by husband of 66 years, Eugene B. Koon; parents; brothers, Arnold, Alfred Jr., Arling, and Philip Delhay; sister Marguerite Delhay Barnes; and granddaughter Gabrielle Czolgos. Surviving her is brother, Jerry D. (Pat) Delhay, of Eagle; sister-in-law Lorraine Delhay of Temple, Texas; daughters, Virginia Haruf of Longmont, Col., Janice Reed, and Debra (Fred) Little, both of Lincoln; grandchildren, Sorel Haruf of Longmont, Col., Whitney Haruf (Charlene Barina) of Denver, Chaney Haruf (Michael) Matsukis of Colorado Springs, Chad (Tiffany) Reed of Shelbyville, Tenn., Dr. Trent (Athena) Reed of Chicago, Ill., Ashlee Reed (Michaela Crowley) of Boston, Mass., Sara (John) Burden of Lincoln, Lyndsie (LC) Coleman of Greeley, Col., and Michael Stephens of Lincoln; great grandchildren, Evan Reed of Shelbyville, Tenn., Mayla Haruf Arnold of Longmont, Col., Preston and Trifon Reed of Chicago, Ava Stephens of Lincoln, and Judah Burden of Lincoln; and numerous nieces, nephews, and friends. Funeral service will be at 10 am Saturday, Oct. 19, with Pastor Larry Moffet officiating, at First United Methodist Church, 2723 N. 50th St. Visitation will be 12-7 pm Friday, with family greeting from 5-7 pm, Lincoln Memorial Funeral Home, 6800 S. 14th St. Interment will be at 1 pm Saturday, following a luncheon at the church, Lincoln Memorial Park, with guests meeting at Gate 2 for procession to graveside. Memorials can be given to First UMC to be used towards the church's new organ. |

Back to Pioneer Photographs.

This page is maintained by M.D. Monk.