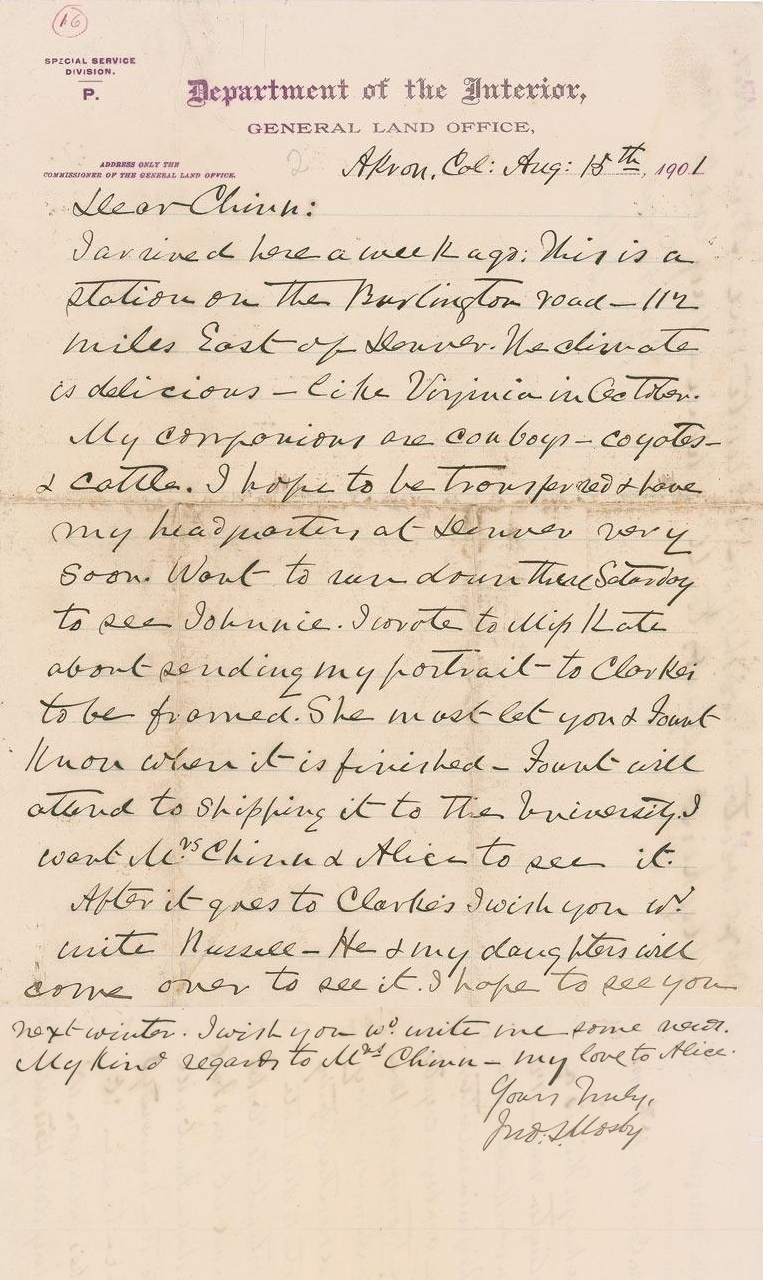

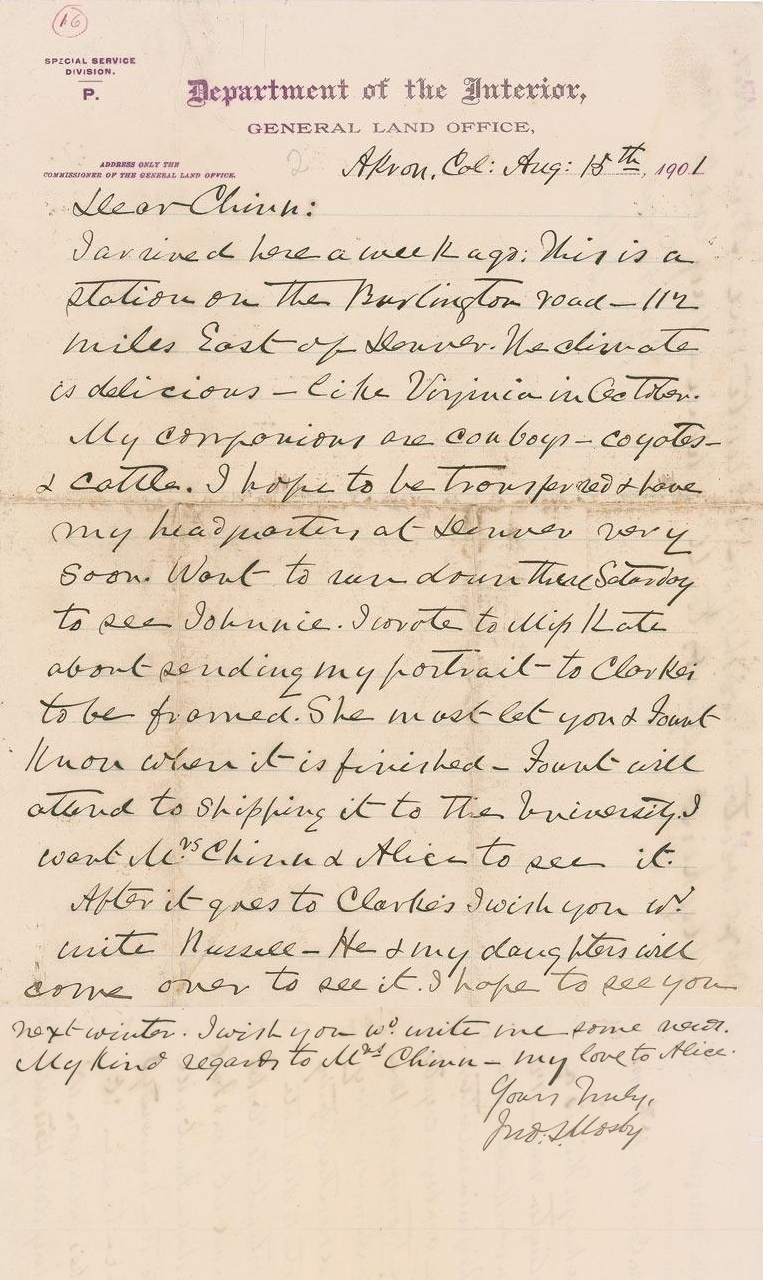

Letter to from Mosby to Chinn dated August 15, 1901, on a Department of the Interior letterhead

written from Akron, Colorado.

“Chinn ” likely was Benton Chinn a member of his Civil War company and

"longtime Eastern factotum" (factotum - a servant employed to do a variety of jobs).

See Benton Chinn obituary below.

The letter reads, in part:

October 25, 1901 Fort Morgan, Colorado " Col. Mosby of war fame, now special officer under the U. S. Interior department, came up from Akron to this county last week in his office capacity, leaving Fort Morgan for home Monday night."

January 31, 1902 Holyoke, Colorado "Colonel J. S. Mosby a noted confederate cavalry officer of the civil war, was in Holyoke Wednesday on business for the Interior Department. Colonel Mosby is a very interesting talker and especially so on all questions connected with the ; civil war on which he is thoroughly posted. He was raised a whig and was a strong unionist up to the time of the beginning of the civil war when he took sides with his people of Virginia for the Confederacy and enlisted as a private and before the close of the war was commissioned of Colonel. After the close of' the war he affiliated politically with the republican party and supported Gen. Grant for president in both campaigns. General Grant offered him a government office which he declined for the reason that he could not afford to leave his law practice. He afterwards accepted an appointment by President Hayes as Consul to Hong Kong, China which office he held till removed by President Cleveland for political reasons. For sixteen years Colonel Mosby held the position as attorney for the Southern Pacific R. R. and made his home in San Francisco till the reorganization of the western roads made a change in attorney's. Colonel Mosby now holds a position in the Interior Department."

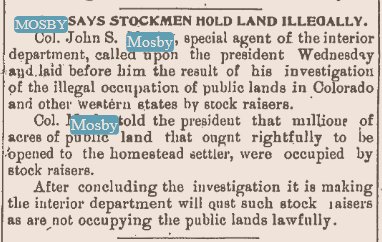

October 24, 1902 "Col. John S. Mosby, special agent of the interior department, called upon the president Wednesday and laid before him the result of his investigation of the illegal occupation of public lands in Colorado and other western states by stock raisers.

Col. Mosby told the president that millions of acres of public land that ought rightfully to be opened to the homestead settler, were occupied by stock raisers. After concluding the investigation it is making, the interior department will oust such stock raisers as are not occupying the public lands lawfully."

The letter reads, in part:

“I arrived here a week ago. This [Akron] is a station on the Burlington road—112 miles east of Denver. The climate is delicious—like Virginia in October. My companions are cowboys—coyotes—& cattle. I hope to be transferred & have my headquarters at Denver very soon…I wrote to Miss Kate about sending my portrait to Clarke’s to be framed.

October 25, 1901 Fort Morgan, Colorado " Col. Mosby of war fame, now special officer under the U. S. Interior department, came up from Akron to this county last week in his office capacity, leaving Fort Morgan for home Monday night."

January 31, 1902 Holyoke, Colorado "Colonel J. S. Mosby a noted confederate cavalry officer of the civil war, was in Holyoke Wednesday on business for the Interior Department. Colonel Mosby is a very interesting talker and especially so on all questions connected with the ; civil war on which he is thoroughly posted. He was raised a whig and was a strong unionist up to the time of the beginning of the civil war when he took sides with his people of Virginia for the Confederacy and enlisted as a private and before the close of the war was commissioned of Colonel. After the close of' the war he affiliated politically with the republican party and supported Gen. Grant for president in both campaigns. General Grant offered him a government office which he declined for the reason that he could not afford to leave his law practice. He afterwards accepted an appointment by President Hayes as Consul to Hong Kong, China which office he held till removed by President Cleveland for political reasons. For sixteen years Colonel Mosby held the position as attorney for the Southern Pacific R. R. and made his home in San Francisco till the reorganization of the western roads made a change in attorney's. Colonel Mosby now holds a position in the Interior Department."

October 24, 1902 "Col. John S. Mosby, special agent of the interior department, called upon the president Wednesday and laid before him the result of his investigation of the illegal occupation of public lands in Colorado and other western states by stock raisers.

Col. Mosby told the president that millions of acres of public land that ought rightfully to be opened to the homestead settler, were occupied by stock raisers. After concluding the investigation it is making, the interior department will oust such stock raisers as are not occupying the public lands lawfully."

June 28, 1901.

June 28, 1901.

Miscellaneous excerpt:

In May 1902 the Rattler reported “U.S. Land Inspector Col. Mosby, of Washington, arrived in Haigler [Nebr] Tuesday night.”

May 1902

October 24, 1902

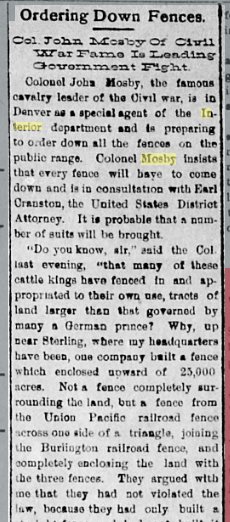

Newspaper article, source unknown:

July 1910 "Col. John S. Mosby, who distinguished himself in the Confederate cause during the Civil war as a daring guerilla fighter and who in the early part of President Roosevelt's administration was appointed a special attorney for the department of justice, has lost his government position. The reason has not been made public, but it is thought old age was the cause for the dismissal. Colonel Mosby is 73 years old, but his friends say he is still active and energetic. He has made no appeal to be restored, although this is deemed probable, and the president and the attorney general may be asked to intervene. The colonel, it is stated, may devote his time to writing a book on the Civil war."

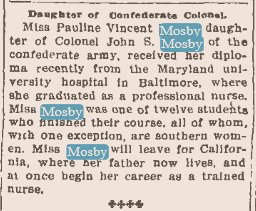

September 3 1915 "John S. Mosby, Jr of Washington, DC well known in Denver and Colorado as Jack Mosby, former lawyer, newspaperman and educator, died at the emergency hospital, Washington, aged 51."

John Jr. is a lawyer in Denver in 1900, single, in a boarding house.

John Singleton Mosby Jr. BIRTH 8 Dec 1863 Warrenton, Fauquier County, Virginia, DEATH 26 Aug 1915 (aged 51) District of Columbia, BURIAL Warrenton Cemetery Warrenton, Fauquier County, Virginia, MEMORIAL ID 6154717

June 1916 Holyoke, Colorado "Colonel John S. Mosby, the famous confederate cavalry raider of the civil war died at Washington, D. C., on May 30, Memorial day, age 82 years. He was known to a number of our people in Phillips county as for some time he held a position with the Interior Department and was sent to Colorado to look after stock men who had been fencing government land in violation of law and he was in our county a few times on this business."

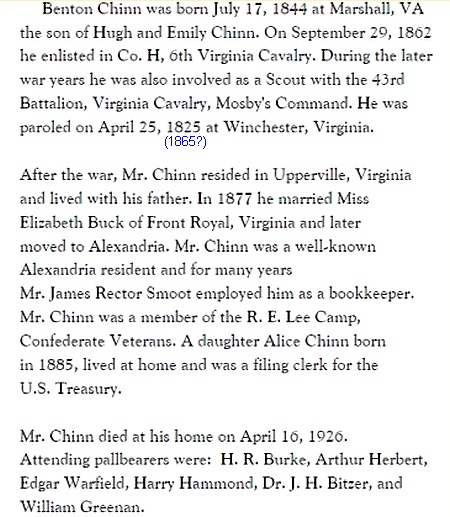

Benton Chinn Obituary